Weight and Glide Distance of an Aicraft

Introduction

Flying is governed by the laws of physics, from aerodynamics to structural dynamics, propulsion, and more. These laws, theories, and equations are critical to understand exactly how aircraft and flying works. However piloting generally requires learning, memorizing, and being able to quickly and reliably apply some relatively simple rules of thumb that have been distilled from theory. The safety of the pilot and their passengers depends on it.

A significant part being a safe pilot is knowing the correct response when encountering emergency scenarios, a common one being engine failure during flight. In this scenario the procedures generally dictate that an attempt to restart the engine be made. In a single engine aircraft, if an engine restart is not possible, the plane and its occupants will inevitably return to the ground. The concern of the pilot then becomes how to execute an emergency landing as safely as possible.

One of the main considerations when executing an emergency landing is finding a suitable landing spot within the maximum glide distance of the aircraft. While the wind, terrain, and many other factors are important considerations, it is critical to understand the behavior of the gliding aircraft to be able to safely pilot it to the ground. The remainder of this post uses some simple equations from physics to give insight into how fast and how far a gliding aircraft will go as it glides. Specifically, I wanted to use these equations to help give some understanding to the perhaps counterintuitive fact that the glide distance of an aircraft is independent of its weight.

Maximum Glide Distance

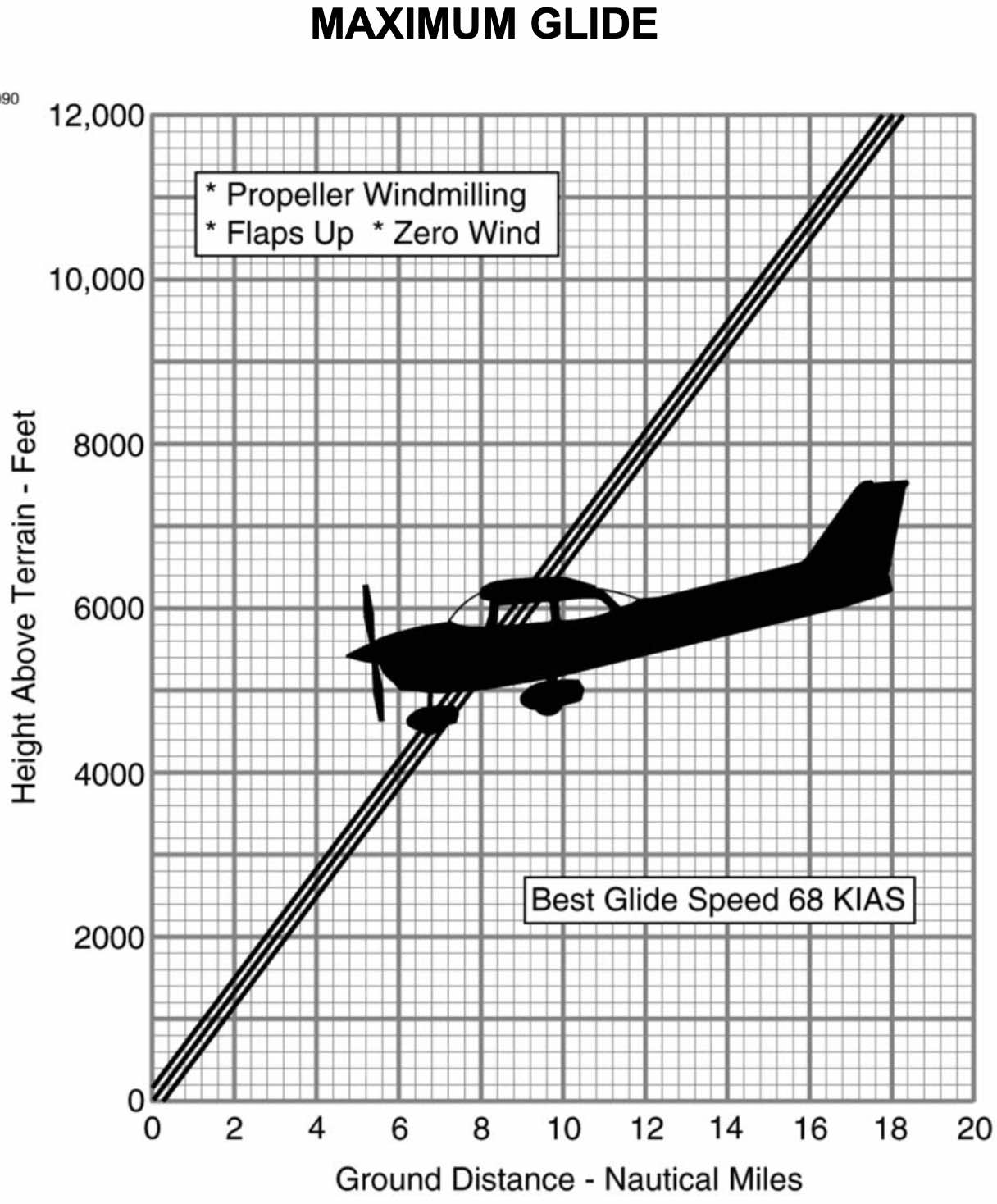

Consider following chart from the emergency procedures section of the aircraft information manual for the Cessna 172.

This chart gives the maximum glide distance based on the height of the aircraft in feet above ground level, or AGL. It is linear, and from this the pilot can see the slope: this Cessna 172 can glide a maximum of 1.5 nm per 1000 feet AGL. This glide ratio is one of two critical numbers from this chart that the pilot should to commit to memory and be to recall immediately should an engine-out scenario arise. The second important number on this chart is best glide speed which tells the pilot to glide at 68 knots indicated airspeed in order to achieve the maximum glide distance.

So if the aircraft is at 6,000 feet AGL and the engine dies, the pilot knows to immediately fly the aircraft at 68 KIAS and can then quickly and effortlessly calculate that they will be able to glide up to 9 nm. Taking into account wind and other environmental factors this gives clear guidance to the pilot where to look for a suitable place to execute an emergency landing.

Note that the glide distance and best glide speed do not depend on the aircraft weight even though many other performance characteristics, such as rate of climb, do. It may be tempting to assume this is just an approximation for such a small aircraft with a narrow operating envelope.

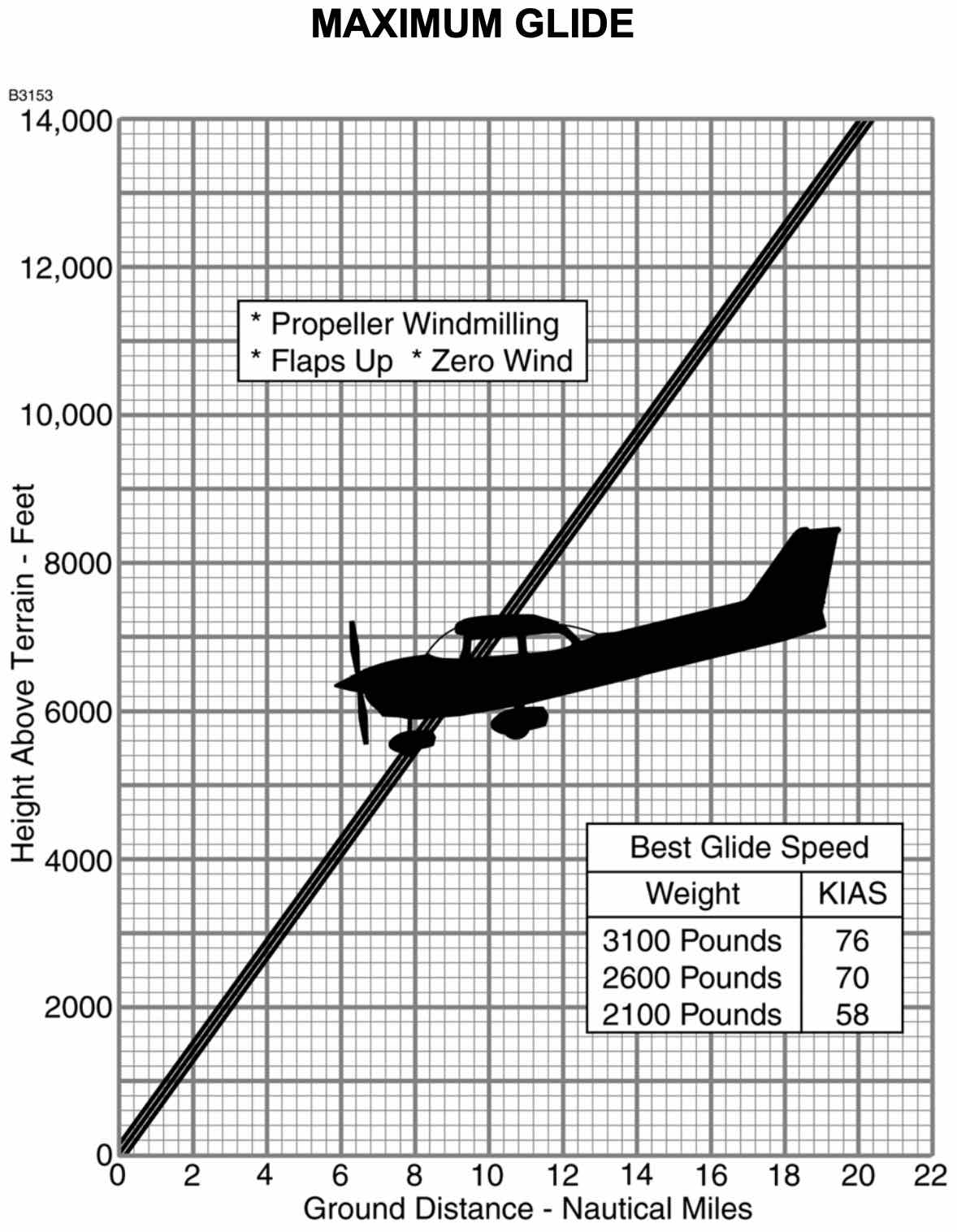

Consider now the information manual from the slightly larger Cessna 182. This is very similar to that of the 172, except that the glide ratio is closer to 1.4 nm per thousand feet AGL.

More importantly though is that the best glide speed does depend on the aircraft weight even though the maximum glide distance does not. And this dependence is quite large—the best glide speed increases 31% between 2100 lb and 3100 lb. So what’s going on? Why is there not a corresponding change of 31% in glide distance as the weight goes up? And does it not seem unexpected that the glide distance does not get worse as the aircraft gets heavier?

This is a question that maybe isn’t so important for the pilot to understand as their directive does not change—fly at the best glide speed, calculate the maximum glide distance, and glide to a location within that radius. But it is an interesting question, and the following simple derivation can give the answer and help provide some insight.

Derivation

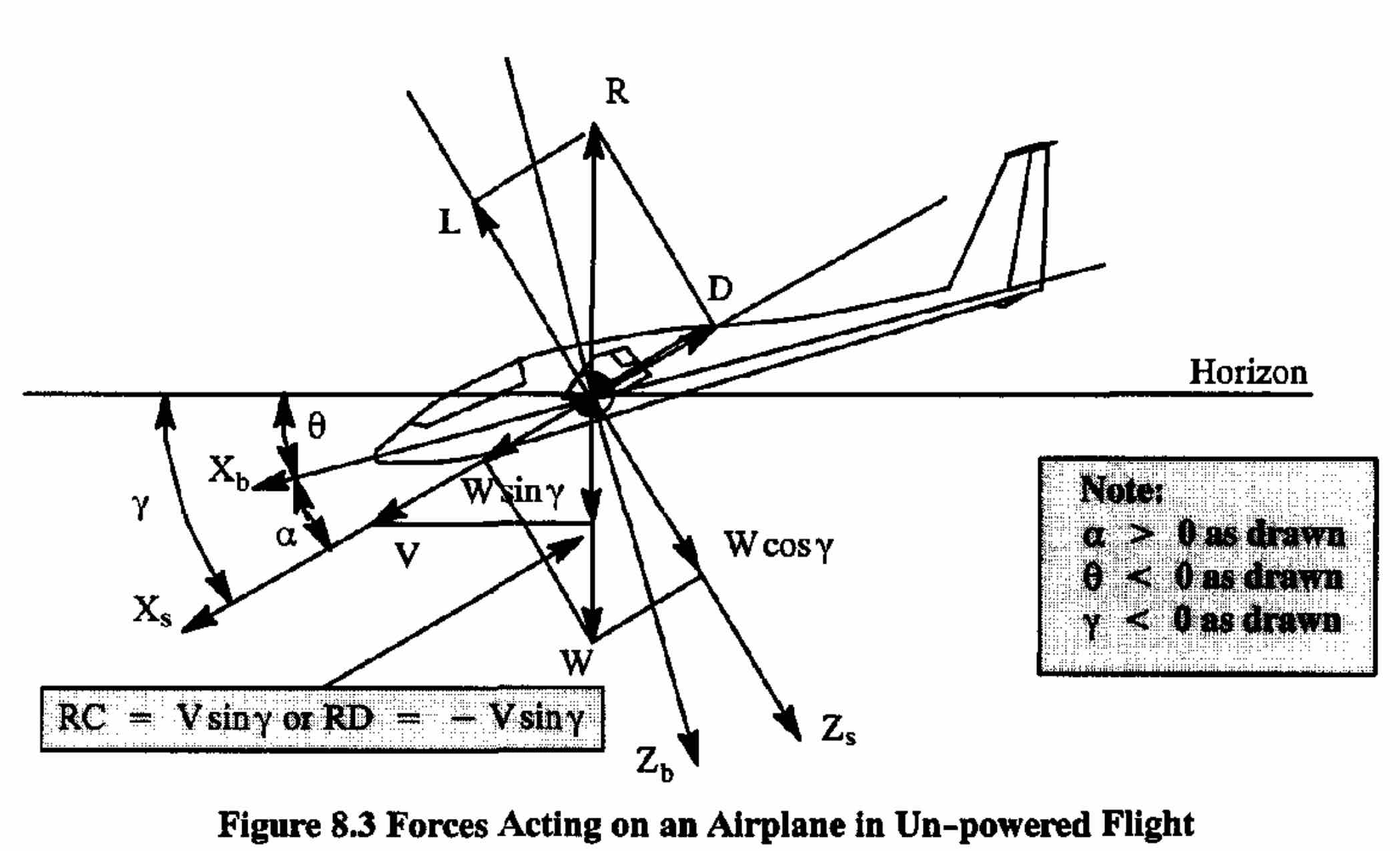

Consider following free-body diagram of a glider (an aircraft with failed engine) from Airplane Aerodynamics and Performance by Jan Roskam.

Note: $RC$ is rate of climb, $RD$ is rate of descent, and $RC=-RD$. The angle of attack is given by $\alpha$, the pitch angle by $\theta$, and the flight path angle by $\gamma$. The lift, drag, and weight are denoted $L$, $D$, $W$, respectively. $X$ and $Z$ are the aircraft axes, with $b$ representing the body-axes, and $s$ the stability axes.

As this diagram represents a gliding aircraft thrust is zero. The only forces acting on the aircraft are lift, drag, and weight, and as the aircraft glides to the ground these forces must balance. This balance in the stability-axis system is given by

\begin{align} \label{eqn.glidedistance.L} L&=W\cos(\gamma) \\ \label{eqn.glidedistance.D} D&=W\sin(\gamma) \end{align}

With the aircraft at altitude above ground given by $h$, the relationship between the flight path angle glide distance $d$ is given by

\begin{equation} \label{eqn.glidedistance.tangamma} \tan(\gamma)=\frac{h}{d} \end{equation}

Using \eqref{eqn.glidedistance.L} and \eqref{eqn.glidedistance.D} the equation in \eqref{eqn.glidedistance.tangamma} can be rearranged to obtain the following expression for the glide distance

\begin{equation} \label{eqn.glidedistance.d} d=h\frac{L}{D} \end{equation}

Lift and drag are related to their corresponding nondimensional coefficients as follows, where $\rho$ is air density and $S$ is the planform area of the wing.

\begin{align} \label{eqn.glidedistance.CL} C_{L}&=\frac{L}{\frac{1}{2}\rho V^{2}S} \\ \label{eqn.glidedistance.CD} C_{D}&=\frac{D}{\frac{1}{2}\rho V^{2}S} \end{align}

Using \eqref{eqn.glidedistance.CL} and \eqref{eqn.glidedistance.CD} and maximizing the glide distance $d$ in \eqref{eqn.glidedistance.d} gives

\begin{equation} \label{eqn.glidedistance.dmax} d_{\max}=h\left(\frac{C_{L}}{C_{D}}\right)_{\max} \end{equation}

So now it can be easily see from \eqref{eqn.glidedistance.dmax} that the glide distance is not dependent on $W$ at all. Rather it depends only on the aerodynamic properties of the aircraft—lift and drag specifically. For a small sub-sonic general aviation aircraft like a Cessna, operating only at low altitudes in Earth’s atmosphere, $C_{L}$ and $C_{D}$ depend only on angle of attack $\alpha$. The relationship between them and thus the maximization of the lift versus the drag coefficient can be read directly from the aircraft’s Drag Polar. The drag polar is not provided in the Aircraft Information Manual, but it is something very well characterized by the aircraft manufactuer, and used to presribe $d_{\max}$ in the maximum glide charts shown above.

Best Glide Speed

The maximization of $C_{L}$ with respect to $C_{D}$ fixes both values of these coefficients, and by looking at \eqref{eqn.glidedistance.CL} the remaining unknowns in the best glide scenario are $L$ and $V$. As lift depends on weight, it is thus expected that the best glide speed depends on weight. The following will show this relationship.

In the earth-axis system the forces on the aicraft can be described by the balanced as follows.

\begin{align*} W &= L\cos(\gamma)+D\sin(\gamma) \\ D\cos(\gamma) &= L\sin(\gamma) \end{align*}

Using some trig identities or use the Pythagorean theorem with the diagram above, the following equation relating weight, lift, and drag can be found.

\begin{equation*} W^{2} = L^{2}+D^{2} \end{equation*}

Using the nondimensional coefficients \eqref{eqn.glidedistance.CL} and \eqref{eqn.glidedistance.CD} the weight can be expressed as

\begin{equation*} W = \frac{1}{2}\rho V^{2}S\sqrt{C_{L}^{2}+C_{D}^{2}} \end{equation*}

From this expression the velocity $V$ can be solved for as

\begin{equation} \label{eqn.glidedistance.V} V = \sqrt{\frac{2W}{\rho S\sqrt{C_{L}^{2}+C_{D}^{2}}}} \end{equation}

From \eqref{eqn.glidedistance.V} it is clear to see that the glide speed varies with the square root of the weight $W$.

Understanding the Result

The above equations and derivations were quite straightforward and simple—a balancing of forces with some trigonometry and aerodynamic relationships. They provide some insight into the dynamics of a gliding aircraft but even still may not necessarily be entirely convincing. Somehow it may still feel like weight is a harmful effect, pulling the aircraft more quickly to the ground, and that a light aircraft should glide farther than a heavy one. But the weight of the aircraft is actually necessary—it is the effective propulsion of the gliding aircraft which can be seen in the diagram above. There is a component of weight that is aligned with velocity. In fact, if weight was zero, the aircraft would remain stationary at altitude, and not only never reach the ground, but also make no forward movement. It would float in place in the atmosphere like a blimp with no engines. So somehow at least some weight is required to glide. But if weight is required for forward movement when gliding, why is more weight not better than less? And why still is the maximum glide distance not dependent on weight?

Considering the unpowered aircraft at altitude $h$, it is important to first recognize that the initial energy of the aicraft, primarily potential, is directly proportional to its weight. Furthermore, this energy is ultimately lost to drag as the aircraft glides to the ground. These unproductive drag losses should be minimized and the productive force generation, lift, maximized. It is aerodynamic efficiency that governs the balance of these forces, and thus the productive conversion of potential energy to lift and drag, and therefore defines the best glide angle. The smaller the drag is relative to lift, the smaller the component of weight (defined by the glide angle) needs to offset the drag. Obviously adding weight to the aircraft does not change its aerodynamic properties and so will not change the best glide angle. But increasing the weight of the aircraft increases it’s initial energy proportionally which will be lost to drag during gliding. And with the best glide angle defined by the aerodynamic properties, it makes sense that the heavier aircraft will simply traverese this same glide angle more quickly. So more weight is only better in the sense that the heavier aircraft will not glide any farther than a light one, but it will arrive there sooner.

Hopefully this simple derivation and discussion has helped to explain and make sense of the fact that the maximum glide distance of an aircraft is not dependent on it’s weight.